An infographic about the prevalence of lactose intolerance

It occurred to me after my (arrogant or precocious, you decide which) effort to remove the lactose from a beautifully elegant French recipe for glissade that I realized that you, my lovely reader, may not care if lactose is in your food or not. I'll give you a couple quick reasons to take at least a little interest:

• reducing lactose in your diet may help you feel a million times better, and

• being able to serve lactose free meals is a classy gesture for guests or family members who may be lactose intolerant.

Here's the deal with lactose. Babies are born with the ability to digest lactose, a major component of milk, but many adults lose this ability as we age. When adults who cannot process lactose eat or drink dairy products they get all kinds of gut discomfort, including possibly gas, bloating, abdominal pain, nausea and watery diarrhea.1,2 The best long term treatment is avoiding dairy in the diet.2

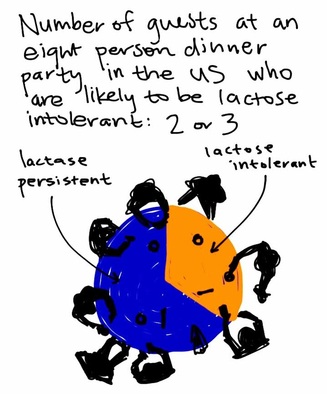

The most interesting thing about lactose intolerance as a pathology is that its not a pathology. It's actually the norm worldwide; about 75% of the world's adults don't produce the enzyme necessary to break down milk. It is also more common among people of Asian, Hispanic and African descent, as well as Native Americans, (which makes it a bit of a structural racism issue that the USDA--not to mention the standard American diet--still recommends three cups of milk per day for all adults...but I digress).1,2

A more accurate description of the situation is to use the term lactase persistent for the lucky, rare adults who still produce this lactose-busting enzyme and can go to town on a glass of milk without incurring digestive trouble.

• reducing lactose in your diet may help you feel a million times better, and

• being able to serve lactose free meals is a classy gesture for guests or family members who may be lactose intolerant.

Here's the deal with lactose. Babies are born with the ability to digest lactose, a major component of milk, but many adults lose this ability as we age. When adults who cannot process lactose eat or drink dairy products they get all kinds of gut discomfort, including possibly gas, bloating, abdominal pain, nausea and watery diarrhea.1,2 The best long term treatment is avoiding dairy in the diet.2

The most interesting thing about lactose intolerance as a pathology is that its not a pathology. It's actually the norm worldwide; about 75% of the world's adults don't produce the enzyme necessary to break down milk. It is also more common among people of Asian, Hispanic and African descent, as well as Native Americans, (which makes it a bit of a structural racism issue that the USDA--not to mention the standard American diet--still recommends three cups of milk per day for all adults...but I digress).1,2

A more accurate description of the situation is to use the term lactase persistent for the lucky, rare adults who still produce this lactose-busting enzyme and can go to town on a glass of milk without incurring digestive trouble.

But this post is really about cheese. Why? Because although we all react differently to lactose, most people who are lactose intolerant can handle about the equivalent of a cup of milk per day without symptoms. But, there is a lot of variability in how much lactose remains in diary products so the trick is to choose our cheeses wisely.1,2

Personally, I like to create and eat lactose free recipes because it actually helps keep food interesting (otherwise, I might use the cheese crutch and throw it in everything). But if I'm going to eat cheese here's the strategy I use:

1. Know what sources generally have less lactose.

Generally, the more aged, the more cultured and the higher the fat content in a dairy food, the less lactose it will contain. So fresh cheeses will contain more lactose than aged cheeses. Yogurt, which is cultured, will contain less lactose than milk. My favorite outcome of this general rule is that higher fat cheeses and yogurts contain less lactose. Did you notice that? Higher fat--more delicious--cheeses contain less lactose. Total score! Also, Butter has very little lactose, and lastly, goat cheese is usually better tolerated as well.

2. Buy high quality products.

You never know about the practices of manufacturers; some manufacturers may add milk back into cheeses, which defeats the whole purpose of choosing cheese to avoid high amounts of lactose. I like to buy high quality, locally produced cheeses from cheesemakers that produce on a small scale. After some trial and error, I've developed some trust in a a few brands.

3) Savor these glorious cheeses, and enjoy them in smaller quantities.

Because cheese is a condensed form of milk, it's still possible to OD on lactose by eating too much of it. Eating less cheese doesn't have to feel depriving though. For example, instead of high-cheese meals like pizza or macaroni and cheese, I usually go for something higher in vegetables, topped with an ounce or less of very nice cheese. Helps me feel normal on the insides, but allows me to go for the glorious cheese too.

Sources:

1. Medscape for iPad app

2. The Merck Manual - Professional Addition app

Personally, I like to create and eat lactose free recipes because it actually helps keep food interesting (otherwise, I might use the cheese crutch and throw it in everything). But if I'm going to eat cheese here's the strategy I use:

1. Know what sources generally have less lactose.

Generally, the more aged, the more cultured and the higher the fat content in a dairy food, the less lactose it will contain. So fresh cheeses will contain more lactose than aged cheeses. Yogurt, which is cultured, will contain less lactose than milk. My favorite outcome of this general rule is that higher fat cheeses and yogurts contain less lactose. Did you notice that? Higher fat--more delicious--cheeses contain less lactose. Total score! Also, Butter has very little lactose, and lastly, goat cheese is usually better tolerated as well.

2. Buy high quality products.

You never know about the practices of manufacturers; some manufacturers may add milk back into cheeses, which defeats the whole purpose of choosing cheese to avoid high amounts of lactose. I like to buy high quality, locally produced cheeses from cheesemakers that produce on a small scale. After some trial and error, I've developed some trust in a a few brands.

3) Savor these glorious cheeses, and enjoy them in smaller quantities.

Because cheese is a condensed form of milk, it's still possible to OD on lactose by eating too much of it. Eating less cheese doesn't have to feel depriving though. For example, instead of high-cheese meals like pizza or macaroni and cheese, I usually go for something higher in vegetables, topped with an ounce or less of very nice cheese. Helps me feel normal on the insides, but allows me to go for the glorious cheese too.

Sources:

1. Medscape for iPad app

2. The Merck Manual - Professional Addition app

RSS Feed

RSS Feed